knightedsoldier5000

Mentor

Until the introduction of strikes just a year prior, pitchers were only a cog in the machine that was a baseball game.

That day, Creighton utilized speed that had never been seen before in baseball. He would deliver pitches with such velocity that opposing managers argued that what he was doing was illegal. According to accounts at the time, Creighton was throwing illegal pitches by snapping his wrist, but it was so slight it couldn’t possibly be picked up by the human eye. In addition, Creighton introduced pitches with spin, as well as a slower pitch called “the dew drop.” Although he was not the first to attempt to add speed, Creighton was the first to successfully and consistently control it. With the introduction of the “strike” just a year before, this was a perfect storm that led Creighton to become the best pitcher baseball had seen to that point.

Creighton’s 1862 season may have been his finest. Both at the plate and on the bases, he was put out only four times. His spectacular pitching continued. However, this season would end in tragedy for Creighton.

On October 14, 1862, Creighton was experiencing another great game, this time against the Unions of Morrisania. In the first five innings, he was 4-for-4 with 4 doubles, as well as a flawless second base. In the top of the sixth inning, he came in to pitch in relief. In the bottom half of the inning, according to those witnessed to the event, Creighton belted a home run in his fifth at bat. But, this home run would turn out to be deadly.

John Chapman, a witness to the game, wrote 50 years later: ““I was present at the game between the Excelsiors and the Unions of Morrisania at which Jim Creighton injured himself. He did it in hitting out a home run. When he had crossed the [plate] he turned to George Flanley and said, ‘I must have snapped my belt,’ and George said, ‘I guess not.’ It turned out that he had suffered a fatal injury. Nothing could be done for him, and baseball met with a severe loss. He had wonderful speed, and, with it, splendid command. He was fairly unhittable.”

In the early days of baseball, a baseball swing involved keeping one’s arms completely straight and violently torquing the hips and abdomen through. It was believed that Creighton swung with such violence that it caused a ruptured inguinal hernia (at the time it was credited as a ruptured bladder).

For the next four days, Creighton suffered from hemorrhaging and internal bleeding. He would pass away on October 18, 1862 at the age of 21. He is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn. A 12-foot marble obelisk stands at his burial site.

Creighton is considered by many historians and baseball enthusiasts as the game’s first superstar. He was involved in many firsts within the game, outside of the evolution of the fastball. Creighton also helped in turning baseball’s first recorded triple play on September 22, 1860, and threw the first recorded shutout on November 8, 1860. In addition, he also put up staggering numbers for his time.

Read more at:

oddsportsstories.com

oddsportsstories.com

That day, Creighton utilized speed that had never been seen before in baseball. He would deliver pitches with such velocity that opposing managers argued that what he was doing was illegal. According to accounts at the time, Creighton was throwing illegal pitches by snapping his wrist, but it was so slight it couldn’t possibly be picked up by the human eye. In addition, Creighton introduced pitches with spin, as well as a slower pitch called “the dew drop.” Although he was not the first to attempt to add speed, Creighton was the first to successfully and consistently control it. With the introduction of the “strike” just a year before, this was a perfect storm that led Creighton to become the best pitcher baseball had seen to that point.

Creighton’s 1862 season may have been his finest. Both at the plate and on the bases, he was put out only four times. His spectacular pitching continued. However, this season would end in tragedy for Creighton.

On October 14, 1862, Creighton was experiencing another great game, this time against the Unions of Morrisania. In the first five innings, he was 4-for-4 with 4 doubles, as well as a flawless second base. In the top of the sixth inning, he came in to pitch in relief. In the bottom half of the inning, according to those witnessed to the event, Creighton belted a home run in his fifth at bat. But, this home run would turn out to be deadly.

John Chapman, a witness to the game, wrote 50 years later: ““I was present at the game between the Excelsiors and the Unions of Morrisania at which Jim Creighton injured himself. He did it in hitting out a home run. When he had crossed the [plate] he turned to George Flanley and said, ‘I must have snapped my belt,’ and George said, ‘I guess not.’ It turned out that he had suffered a fatal injury. Nothing could be done for him, and baseball met with a severe loss. He had wonderful speed, and, with it, splendid command. He was fairly unhittable.”

In the early days of baseball, a baseball swing involved keeping one’s arms completely straight and violently torquing the hips and abdomen through. It was believed that Creighton swung with such violence that it caused a ruptured inguinal hernia (at the time it was credited as a ruptured bladder).

For the next four days, Creighton suffered from hemorrhaging and internal bleeding. He would pass away on October 18, 1862 at the age of 21. He is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn. A 12-foot marble obelisk stands at his burial site.

Creighton is considered by many historians and baseball enthusiasts as the game’s first superstar. He was involved in many firsts within the game, outside of the evolution of the fastball. Creighton also helped in turning baseball’s first recorded triple play on September 22, 1860, and threw the first recorded shutout on November 8, 1860. In addition, he also put up staggering numbers for his time.

Read more at:

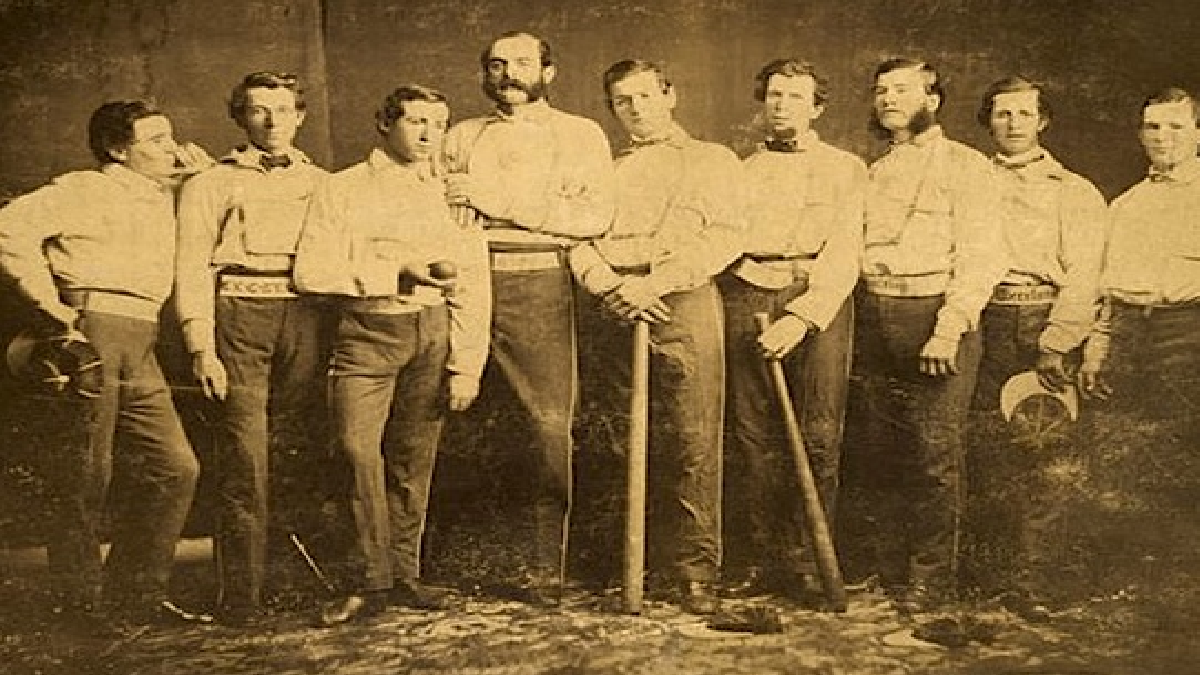

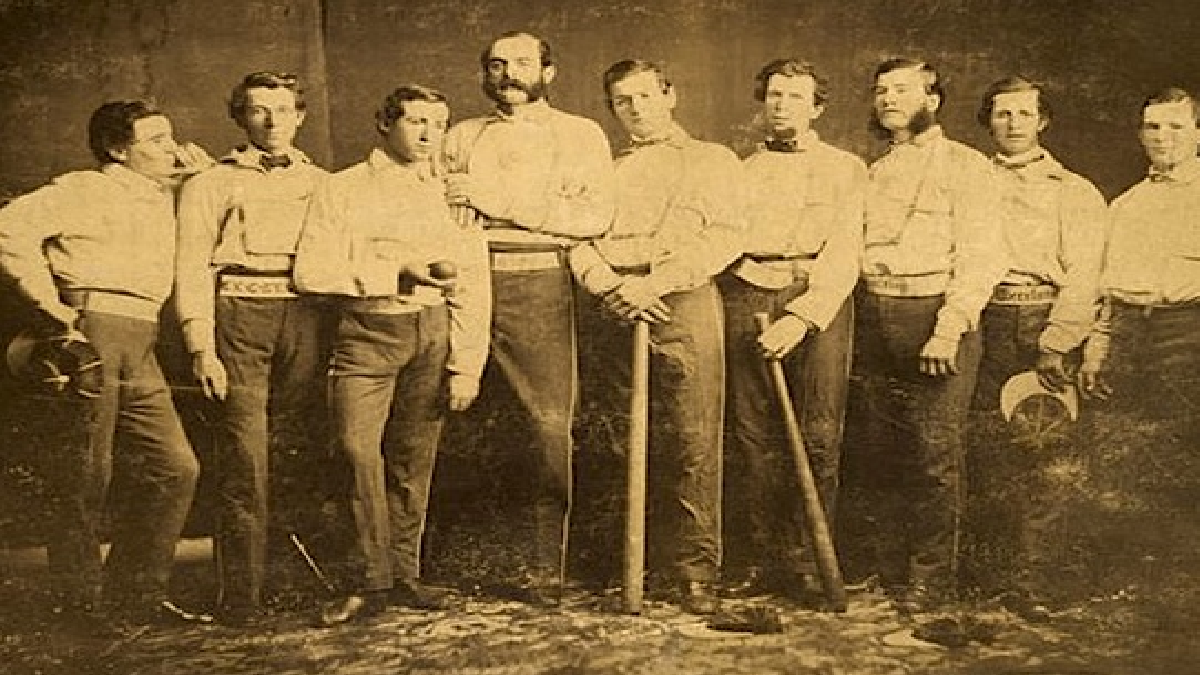

Jim Creighton: Baseball’s First Superstar

James “Jim” Creighton, Jr. was born on April 15, 1841. Creighton, over the course of his short life, revolutionized the game of baseball. Creighton was known for making an impact in many aspects of…

oddsportsstories.com

oddsportsstories.com