Colonel_Reb

Hall of Famer

<DIV =story-er>

<H1 =storyTitle> [url]http://sports.espn.go.com/nfl/playoffs07/news/story?id=32092 45[/url]</H1>

<H1 =storyTitle>Super Bowl XVII starter Woodley's life drifted after football</H1>

<DIV =byLine>

By Elizabeth Merrill

ESPN.com

(Archive)

<DIV =sp-clear>

<DIV =promoPlug>

<DIV =sp-clear>

At the end, David Woodley didn't want to sleep. He was afraid he'd never wake up. Alcohol wrecked his liver and his marriage. He was 44, lying in a hospital bed, waiting to die. The muscle and Louisiana charm that first caught the eye of his wife was gone. She once thought he looked like Christopher Reeve, like Superman. When the ball rocketed from his fingertips, receivers hid in warm-ups. Woodley had a gift.

He was 24 when he led the Miami Dolphins onto the field in Super Bowl XVII. Only 51 men have made it to the Super Bowl as starting quarterbacks and, for many, their lives are never the same. They make Hall of Fame speeches and open restaurants. Maybe Woodley did have one thing in common with them. He was never the same, either.

Twenty years after he left that field in Pasadena, Calif., he died, alone, a sliver of the hunk that Suzonne Pugh, his ex-wife, met at a bayou bar in college. He'd apparently driven himself to the hospital. What happened in that lonely gap between the Super Bowl and his death in 2003 will always be confounding.

<DIV =sp-inlinePhoto style="PADDING-RIGHT: 15px; PADDING-LEFT: 15px; PADDING-BOTTOM: 5px; PADDING-TOP: 0px">

<DIV =photoEnlarge>[+] Enlarge

<DIV style="CLEAR: both">

<DIV style="WIDTH: 300px">

MPS/WireImage.com

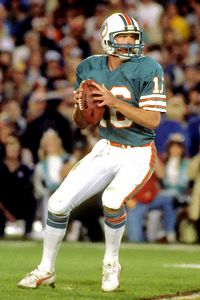

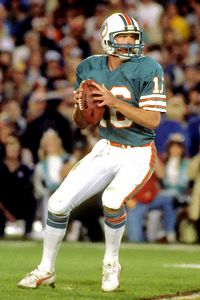

Dolphins coach Don Shula liked quarterback David Woodley's mobility, but it wasn't enough to help Miami beat the Washington Redskins in Super Bowl XVII.

"He was always a loner," says former Miami quarterback Don Strock, who, like most of his teammates, lost touch with Woodley after football. "Came to work and did his job."

Super Bowl quarterbacks like Tom Brady and Eli Manning savor these days, standing on the biggest stage of the sports universe, all eyes on them. For Woodley, it was a job he never wanted but couldn't live without.

"The pressure overwhelmed him," Pugh says. "He drank to try and forget most of it, or make it so it didn't matter that much.

"You know, he could've been happy, and he could've been a great player if ... everybody would've just stepped back and let him be himself."

<HR align=center width=150>

The thing Woodley liked most about football was the pain. At the bottom of a pile, with sweaty behemoths pinching and punching, Woodley felt oddly safe. He broke two ribs once in a game against the Jets. It was one of his best games ever.

He spent eight months out of the year with 50-plus men, sacrificed his body each Sunday with 10 brothers, but rarely revealed details about his life. He grew up in Shreveport, La., with six siblings, but was an introvert. His father was an alcoholic.

Woodley's brother Joe stops short of calling it an unhappy childhood.

"I guess it was OK," he says. "It had its good times and bad times. We had a lot of good times."

Woodley went to LSU, dazzled with his strong arm and quick feet and led the Tigers to a Tangerine Bowl victory. But he ultimately shared time with Steve Ensminger, a local kid from Baton Rouge. Woodley was booed; Ensminger was loved. Woodley never forgot how the crowds hurt him.

In 1980, they called him the sacrificial lamb in Miami because he was young, erratic and had virtually no chance of making the Dolphins' roster. He started training camp at No. 4 on the depth chart. By the end of the season, he'd replaced Bob Griese and broken the club's rookie record with 176 completions.

Coach Don Shula liked Woodley's mobility. If things fell apart, he'd take off running. He never seemed to dwell on a mistake. At least not in front of his teammates.

Off the field, he seemed consumed with the people behind him. He'd slump over his playbook late at night, tired and bloodshot, while Suzonne quizzed him over formations.

"He was always looking over his shoulder," she says.

<DIV =sp-inlinePhoto style="PADDING-RIGHT: 15px; PADDING-LEFT: 15px; PADDING-BOTTOM: 5px; PADDING-TOP: 0px">

<DIV =photoEnlarge>[+] Enlarge

<DIV style="CLEAR: both">

<DIV style="WIDTH: 300px">

John Pineda/Getty Images

Woodley platooned for at time with Dolphins backup Don Strock, seen talking with Bob Griese. The Woodley-Strock combination became known as "Woodstrock."The next season, Shula platooned Woodley with Strock. They were complete opposites.

Strock was the bandleader, the veteran pocket passer, the outgoing teacher who bought the boys drinks after practice. Woodley was the private kid who could come across as standoffish.

But he seemed in control, and took the Dolphins to the Super Bowl in a strike-shortened '82 season. He was just 24.

There was one drawback for Woodley. For one week, he'd have to be in the spotlight.

<HR align=center width=150>

They gathered in Pasadena, Calif., in search of stories and sound bites, and Woodley disappointed the media before he ever took a snap.

"Hey David, you're the youngest Super Bowl quarterback ever. What do you think about that?"

"Not much."

"Hey David ..."

"I don't think he enjoyed any bit of it," former Dolphins receiver Jimmy Cefalo says. "Not a single lick of it.

"He really didn't care what people thought. He wore purple Keds everywhere he went, and then kids started wearing them around town. He'd have some nasty cutoffs, purple sneakers, and a car from 1968. He was just a quiet, unusual guy. He was his own person and didn't give a rat's ass about what anybody thought."

But even if Woodley was dismissing the week with one-word answers, Suzonne, at least, knew it was a big deal. She'd never flown in a plane that huge. She sort of liked the attention and being pampered.

The night the Dolphins arrived in Pasadena for Super Bowl XVII, Strock took a bunch of his teammates out for dinner. Woodley was nowhere to be found. Cefalo figured he was probably holed up in a hotel room, drinking a beer.

<DIV =sp-inlinePhoto style="PADDING-RIGHT: 15px; PADDING-LEFT: 15px; PADDING-BOTTOM: 5px; PADDING-TOP: 0px">

<DIV =photoEnlarge>[+] Enlarge

<DIV style="CLEAR: both">

<DIV style="WIDTH: 200px">

Manny Rubio/US Presswire

"Football was his life," says Woodley's ex-wife, Suzonne Pugh. "He didn't know what to do with his time after that."But when Sunday night finally came, Woodley came out with a purpose. He hit Cefalo with a 76-yard touchdown pass, and the Dolphins had a 17-10 lead at halftime. On the outside, Woodley seemed confident. He always had a tough outer shell.

He threw eight passes in the second half, and misfired on all of them. The Redskins won 27-17, and Woodley was branded one of the worst quarterbacks in the history of the Super Bowl. It would be his only shot. A few months later, the Dolphins drafted wonder kid Dan Marino, and Woodley's name became a trivia question in Miami football history: "Who was the quarterback between Griese and Marino?"

Woodley was traded to Pittsburgh, where he had the misfortune of following another legend in Terry Bradshaw. At least he wasn't alone. Woodley would platoon with Mark Malone.

One day in 1985, an hour before the Steelers played San Diego, Woodley called Suzonne from the locker room. He said he was quitting, right there, because at 27, he'd had enough. She talked him out of it, and he threw three touchdowns that day. He stuck out the rest of the season, then retired.

From there, his drinking veered out of control. He started with beer, lots of it, and eventually numbed his inner anguish with Bacardi rum. That's when things really went downhill. Suzonne went to Al-Anon meetings to try to learn to live with it. In 1986, she decided it had become impossible.

Within months after his retirement, Woodley realized he'd made a huge mistake.

"Football was his life," she says. "He didn't know what to do with his time after that. We had a health club we had bought in Miami, and he just kind of let it go, too. He just didn't have any heart for anything after that."

He did try to go back. One day, he called Suzonne to say he had a tryout with the Packers. But he was released from training camp in 1987 and never played football again.

<HR align=center width=150>

Over nearly two decades, Cefalo said he placed at least 100 phone calls to Woodley. He sent him a plane ticket once so Woodley could fly out from Shreveport to Florida for a TV show honoring Shula. Woodley never picked up the ticket.

About 10 years ago, Cefalo got a strange message on his work phone.

"You told me you wanted me to call you. Well, I've called you."

The caller just hung up. Cefalo had to listen to the message several times before he figured out it was Woodley. It may have been the only contact he had with a teammate in more than a decade.

When Woodley moved back to Shreveport, he put his NFL life far behind him. He drank alone. He had a liver transplant in 1992. He struggled through money problems alone and apparently made no attempts to cash in on his past. The Dolphins would occasionally see him at training camp, trying to peddle jewelry as the players walked to their cars.

<DIV =sp-inlinePhoto style="PADDING-RIGHT: 15px; PADDING-LEFT: 15px; PADDING-BOTTOM: 5px; PADDING-TOP: 0px">

<DIV =photoEnlarge>[+] Enlarge

<DIV style="CLEAR: both">

<DIV style="WIDTH: 200px">

Focus on Sport/Getty Images

In 1983, at the age of 24, Woodley became the youngest starting Super Bowl quarterback to that point.Woodley never wanted to feel beholden to anybody. When he was playing for the Dolphins, a car dealership offered him wheels and money for what amounted to one or two appearances a year. Athletes weren't millionaires back then. Woodley promptly told the dealer no.

"It was a ... they were going to take a part of his soul kind of thing," Cefalo says.

"David didn't care about money and fame. He shunned all of it. It was something thrust upon him. David was a tortured soul, but he had a kindness behind his eyes. He was trying to define himself to himself. He was his own person and trying to figure out what that meant."

<HR align=center width=150>

About six months before he died of complications from liver and kidney disease, Woodley called Suzonne.

"If anything were to ever happen," he said, "I just want you to know how sorry I am."

She'd heard he needed $3,000 worth of medicine a month near the end, but isn't sure he had the money to buy it. Twenty years after he was the youngest quarterback to ever start in a Super Bowl, Woodley became the youngest Super Bowl quarterback to die.

Suzonne says she wasn't invited to the funeral. Most of his teammates didn't even know where it was held.

She won't watch football anymore. It brings back too many bad memories. She's remarried, has two kids and owns a retail flooring store in Baton Rouge, La. Customers stream in, wearing LSU gold and purple. They have no idea who David Woodley once was.

<H1 =storyTitle> [url]http://sports.espn.go.com/nfl/playoffs07/news/story?id=32092 45[/url]</H1>

<H1 =storyTitle>Super Bowl XVII starter Woodley's life drifted after football</H1>

<DIV =byLine>

By Elizabeth Merrill

ESPN.com

(Archive)

<DIV =sp-clear>

<DIV =promoPlug>

<DIV =sp-clear>

At the end, David Woodley didn't want to sleep. He was afraid he'd never wake up. Alcohol wrecked his liver and his marriage. He was 44, lying in a hospital bed, waiting to die. The muscle and Louisiana charm that first caught the eye of his wife was gone. She once thought he looked like Christopher Reeve, like Superman. When the ball rocketed from his fingertips, receivers hid in warm-ups. Woodley had a gift.

He was 24 when he led the Miami Dolphins onto the field in Super Bowl XVII. Only 51 men have made it to the Super Bowl as starting quarterbacks and, for many, their lives are never the same. They make Hall of Fame speeches and open restaurants. Maybe Woodley did have one thing in common with them. He was never the same, either.

Twenty years after he left that field in Pasadena, Calif., he died, alone, a sliver of the hunk that Suzonne Pugh, his ex-wife, met at a bayou bar in college. He'd apparently driven himself to the hospital. What happened in that lonely gap between the Super Bowl and his death in 2003 will always be confounding.

<DIV =sp-inlinePhoto style="PADDING-RIGHT: 15px; PADDING-LEFT: 15px; PADDING-BOTTOM: 5px; PADDING-TOP: 0px">

<DIV =photoEnlarge>[+] Enlarge

<DIV style="CLEAR: both">

<DIV style="WIDTH: 300px">

MPS/WireImage.com

Dolphins coach Don Shula liked quarterback David Woodley's mobility, but it wasn't enough to help Miami beat the Washington Redskins in Super Bowl XVII.

"He was always a loner," says former Miami quarterback Don Strock, who, like most of his teammates, lost touch with Woodley after football. "Came to work and did his job."

Super Bowl quarterbacks like Tom Brady and Eli Manning savor these days, standing on the biggest stage of the sports universe, all eyes on them. For Woodley, it was a job he never wanted but couldn't live without.

"The pressure overwhelmed him," Pugh says. "He drank to try and forget most of it, or make it so it didn't matter that much.

"You know, he could've been happy, and he could've been a great player if ... everybody would've just stepped back and let him be himself."

<HR align=center width=150>

The thing Woodley liked most about football was the pain. At the bottom of a pile, with sweaty behemoths pinching and punching, Woodley felt oddly safe. He broke two ribs once in a game against the Jets. It was one of his best games ever.

He spent eight months out of the year with 50-plus men, sacrificed his body each Sunday with 10 brothers, but rarely revealed details about his life. He grew up in Shreveport, La., with six siblings, but was an introvert. His father was an alcoholic.

Woodley's brother Joe stops short of calling it an unhappy childhood.

"I guess it was OK," he says. "It had its good times and bad times. We had a lot of good times."

Woodley went to LSU, dazzled with his strong arm and quick feet and led the Tigers to a Tangerine Bowl victory. But he ultimately shared time with Steve Ensminger, a local kid from Baton Rouge. Woodley was booed; Ensminger was loved. Woodley never forgot how the crowds hurt him.

In 1980, they called him the sacrificial lamb in Miami because he was young, erratic and had virtually no chance of making the Dolphins' roster. He started training camp at No. 4 on the depth chart. By the end of the season, he'd replaced Bob Griese and broken the club's rookie record with 176 completions.

Coach Don Shula liked Woodley's mobility. If things fell apart, he'd take off running. He never seemed to dwell on a mistake. At least not in front of his teammates.

Off the field, he seemed consumed with the people behind him. He'd slump over his playbook late at night, tired and bloodshot, while Suzonne quizzed him over formations.

"He was always looking over his shoulder," she says.

<DIV =sp-inlinePhoto style="PADDING-RIGHT: 15px; PADDING-LEFT: 15px; PADDING-BOTTOM: 5px; PADDING-TOP: 0px">

<DIV =photoEnlarge>[+] Enlarge

<DIV style="CLEAR: both">

<DIV style="WIDTH: 300px">

John Pineda/Getty Images

Woodley platooned for at time with Dolphins backup Don Strock, seen talking with Bob Griese. The Woodley-Strock combination became known as "Woodstrock."The next season, Shula platooned Woodley with Strock. They were complete opposites.

Strock was the bandleader, the veteran pocket passer, the outgoing teacher who bought the boys drinks after practice. Woodley was the private kid who could come across as standoffish.

But he seemed in control, and took the Dolphins to the Super Bowl in a strike-shortened '82 season. He was just 24.

There was one drawback for Woodley. For one week, he'd have to be in the spotlight.

<HR align=center width=150>

They gathered in Pasadena, Calif., in search of stories and sound bites, and Woodley disappointed the media before he ever took a snap.

"Hey David, you're the youngest Super Bowl quarterback ever. What do you think about that?"

"Not much."

"Hey David ..."

"I don't think he enjoyed any bit of it," former Dolphins receiver Jimmy Cefalo says. "Not a single lick of it.

"He really didn't care what people thought. He wore purple Keds everywhere he went, and then kids started wearing them around town. He'd have some nasty cutoffs, purple sneakers, and a car from 1968. He was just a quiet, unusual guy. He was his own person and didn't give a rat's ass about what anybody thought."

But even if Woodley was dismissing the week with one-word answers, Suzonne, at least, knew it was a big deal. She'd never flown in a plane that huge. She sort of liked the attention and being pampered.

The night the Dolphins arrived in Pasadena for Super Bowl XVII, Strock took a bunch of his teammates out for dinner. Woodley was nowhere to be found. Cefalo figured he was probably holed up in a hotel room, drinking a beer.

<DIV =sp-inlinePhoto style="PADDING-RIGHT: 15px; PADDING-LEFT: 15px; PADDING-BOTTOM: 5px; PADDING-TOP: 0px">

<DIV =photoEnlarge>[+] Enlarge

<DIV style="CLEAR: both">

<DIV style="WIDTH: 200px">

Manny Rubio/US Presswire

"Football was his life," says Woodley's ex-wife, Suzonne Pugh. "He didn't know what to do with his time after that."But when Sunday night finally came, Woodley came out with a purpose. He hit Cefalo with a 76-yard touchdown pass, and the Dolphins had a 17-10 lead at halftime. On the outside, Woodley seemed confident. He always had a tough outer shell.

He threw eight passes in the second half, and misfired on all of them. The Redskins won 27-17, and Woodley was branded one of the worst quarterbacks in the history of the Super Bowl. It would be his only shot. A few months later, the Dolphins drafted wonder kid Dan Marino, and Woodley's name became a trivia question in Miami football history: "Who was the quarterback between Griese and Marino?"

Woodley was traded to Pittsburgh, where he had the misfortune of following another legend in Terry Bradshaw. At least he wasn't alone. Woodley would platoon with Mark Malone.

One day in 1985, an hour before the Steelers played San Diego, Woodley called Suzonne from the locker room. He said he was quitting, right there, because at 27, he'd had enough. She talked him out of it, and he threw three touchdowns that day. He stuck out the rest of the season, then retired.

From there, his drinking veered out of control. He started with beer, lots of it, and eventually numbed his inner anguish with Bacardi rum. That's when things really went downhill. Suzonne went to Al-Anon meetings to try to learn to live with it. In 1986, she decided it had become impossible.

Within months after his retirement, Woodley realized he'd made a huge mistake.

"Football was his life," she says. "He didn't know what to do with his time after that. We had a health club we had bought in Miami, and he just kind of let it go, too. He just didn't have any heart for anything after that."

He did try to go back. One day, he called Suzonne to say he had a tryout with the Packers. But he was released from training camp in 1987 and never played football again.

<HR align=center width=150>

Over nearly two decades, Cefalo said he placed at least 100 phone calls to Woodley. He sent him a plane ticket once so Woodley could fly out from Shreveport to Florida for a TV show honoring Shula. Woodley never picked up the ticket.

About 10 years ago, Cefalo got a strange message on his work phone.

"You told me you wanted me to call you. Well, I've called you."

The caller just hung up. Cefalo had to listen to the message several times before he figured out it was Woodley. It may have been the only contact he had with a teammate in more than a decade.

When Woodley moved back to Shreveport, he put his NFL life far behind him. He drank alone. He had a liver transplant in 1992. He struggled through money problems alone and apparently made no attempts to cash in on his past. The Dolphins would occasionally see him at training camp, trying to peddle jewelry as the players walked to their cars.

<DIV =sp-inlinePhoto style="PADDING-RIGHT: 15px; PADDING-LEFT: 15px; PADDING-BOTTOM: 5px; PADDING-TOP: 0px">

<DIV =photoEnlarge>[+] Enlarge

<DIV style="CLEAR: both">

<DIV style="WIDTH: 200px">

Focus on Sport/Getty Images

In 1983, at the age of 24, Woodley became the youngest starting Super Bowl quarterback to that point.Woodley never wanted to feel beholden to anybody. When he was playing for the Dolphins, a car dealership offered him wheels and money for what amounted to one or two appearances a year. Athletes weren't millionaires back then. Woodley promptly told the dealer no.

"It was a ... they were going to take a part of his soul kind of thing," Cefalo says.

"David didn't care about money and fame. He shunned all of it. It was something thrust upon him. David was a tortured soul, but he had a kindness behind his eyes. He was trying to define himself to himself. He was his own person and trying to figure out what that meant."

<HR align=center width=150>

About six months before he died of complications from liver and kidney disease, Woodley called Suzonne.

"If anything were to ever happen," he said, "I just want you to know how sorry I am."

She'd heard he needed $3,000 worth of medicine a month near the end, but isn't sure he had the money to buy it. Twenty years after he was the youngest quarterback to ever start in a Super Bowl, Woodley became the youngest Super Bowl quarterback to die.

Suzonne says she wasn't invited to the funeral. Most of his teammates didn't even know where it was held.

She won't watch football anymore. It brings back too many bad memories. She's remarried, has two kids and owns a retail flooring store in Baton Rouge, La. Customers stream in, wearing LSU gold and purple. They have no idea who David Woodley once was.